What The Wire Can Teach Us About Cyber Security

The Wire holds plenty of lessons for infosec.

In the current era of self-isolation, remote work, and constant tweets offering epidemiological hot takes, now is the perfect time to get off social media and tuck into a good box set.

Don’t just take my word for it. Disney, Apple, and Netflix have all reduced their streaming quality to deal with the increased demand for streaming. Yet, despite the abundance of series and movies at our fingertips, it can often be surprisingly difficult to choose the right one.

Of course, the correct choice is always The Wire, a delightful subversion of the traditional cop show genre and the undisputed G.O.A.T. of television. Whether it be its interweaving plot lines, richly complex characters, or a screenplay rooted in reality, it’s a box set that really does have it all. It is no surprise that the five series epic has been dubbed the “visual equivalent of a Dickens novel”and described as one of the most significant pieces of art in the last few decades by none other than former President Barack Obama.

Unfortunately, the world of cyber threats continues to evolve during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, there is no shortage of threat actors (or pesky managers) preventing employees from binge-watching TV shows, no matter their critical acclaim.

The good news, however, is that The Wire holds plenty of lessons for infosec. The business case for watching it should, therefore, be easy enough to justify.

Interested?

The Thin Line Between Good and Bad

If The Wire should have taught us anything, it was that neat categories rarely exist. The show excels in demonstrating how the line between the good guys and the bad guys is a blurry one indeed.

Take Jimmy McNulty, a cop who will stop at nothing in his attempt to lock up criminals and protect the streets of Baltimore. McNulty undoubtedly possesses various admirable traits, many of which could apply to an Infosec professional. His doggedness, passion for the cause, and relentless work ethic would all be welcome attributes in a budding cyber threat intelligence (CTI) analyst.

Yet, McNulty is also perfectly willing to lie, cheat, and even drive drunk. Rather than regarding the law as sacrosanct, McNulty is all too willing to bend it to suit his interests. As a policeman who should be setting an example to society, his conduct leaves much to be desired.

It’s not just the good guys who are multifaceted as The Wire also highlights the diverse nature of criminals. For example, the drug kingpin Avon Barksdale was all too happy to donate to a local community boxing club in need while his partner-in-crime Stringer Bell worked relentlessly in an attempt to legitimise their criminal operation. Or say Omar Little – while well acquainted with blowing off peoples’ heads with a 12 gauge shotgun, Mr. Little nevertheless has integrity in buckets, a disdain for swear words, and a clear moral code.

The Baltimore criminal collective also maintained broader community principles. For instance, the various drug dealing crime families upheld a Sunday truce that prohibited the use of violence against rival gang members on the day of the Sabbath.

This blurred line between the good guys and the bad guys also applies to infosec.

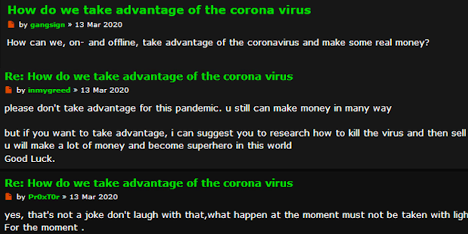

While the significant majority of the cybersecurity community have put out excellent content on the threats related to COVID-19, a minority have not covered themselves in glory in how they have reacted, and even capitalised, on the crisis. Crucially, now is not the time to push F.U.D. (fear, uncertainty, and doubt) at a time when organisations require practical advice and a clear sense of what they should be on the lookout for.

Likewise, it is also important to remember that cybercriminals are people too—many of whom will also be scared for their loved ones. While some cybercriminals will undoubtedly see COVID-19 as an opportunity, others would find the idea of capitalising on the pandemic morally reprehensible. Indeed, it has been encouraging to see prominent ransomware groups stating that they do not intend to target healthcare organisations during this time and will even provide a free decryption tool to any healthcare organisations that they inadvertently affect. Digital Shadows has also observed cybercriminals expressing solidarity with countries severely affected by COVID-19 and discouraging others from profiting off the pandemic.

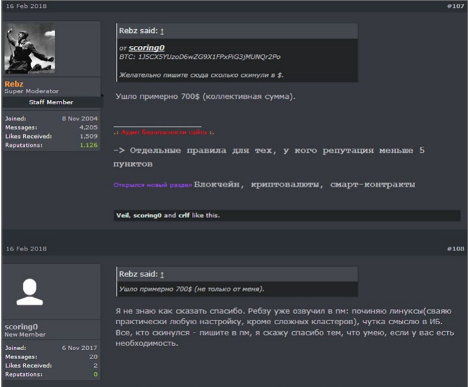

The charitable side of cybercriminals also exists outside of pandemics. In one extraordinary example of forum justice observed on the Russian-language Antichat, a user explained that they needed money to pay for their father’s cancer medication. Antichat administrators eventually arranged a “whip around” among forum members that raised $700 for the medical treatment.

For Criminals, Reputation is King

On the tough streets of Baltimore, reputation is everything. It cements your standing on the criminal ladder and establishes your trustworthiness within the broader community.

Brother Mouzone encapsulates the importance of reputation — a New York enforcer who is also a voracious reader of high-brow magazines. Despite being in the grubby business of killing people and protecting drug empires for a living, Brother Mouzone takes his self-presentation seriously and is always in a suit and bow tie.

Both his reputation and that of his clients are sacrosanct for the New Yorker. It was the word and status of the Barksdale operation that meant Brother Mouzone was willing to work with them in the first place. Likewise, when framed for a murder he did not commit, Brother Mouzone immediately refuses a pay-off to keep him sweet. This is because breaking your word is a crime that goes beyond business.

Reputation is equally crucial for cybercriminals. Establishing a good reputation is arguably even more critical for criminals online.

As argued by University of Oxford academic Dr. Jonathan Lusthaus, if a criminal does not truly know who they are dealing with, it makes it difficult to assess their trustworthiness or to retaliate should dealings go sour and agreements need to be enforced. This creates a large trust deficit, beyond even that common among conventional criminals, and could destabilise cybercriminal transactions.

Online personas and nicknames, therefore, provide a crucial function in helping cybercriminals build their reputation. They provide at least some level of assurance around the product that they are selling (whether that be stolen data, credit card numbers, or malware).

Within the cybercriminal underground, reputation helps to explain the enduring popularity of forums. Forums provide a crucial platform for facilitating communication and cooperation amongst cybercriminals. Forums such as Exploit have been around for a long time and remain popular despite there now being more ostensibly secure alternative forms of communication, which are harder for law enforcement to disrupt. Their history drives the popularity of many criminal forums.

For instance, reputation is a central principle for many of the prominent Russian-language cybercriminal forums operating today, many of which have a long pedigree. The status of these established cybercriminal forums—and the prestige associated with being a forum member—is attractive to many threat actors. Linking to a profile on a hallowed forum is an almost failsafe way for cybercriminals to prove their credibility and legitimacy.

Within these forums, reputation also goes a long way for individuals. When one of the administrators of the prestigious DamageLab forum, Sergey Yarets (also known by the username Ar3s), was arrested in December 2017, the remaining members of the forum team closed the site down to protect the forum’s members. Many months later, the former administrator of Exploit forum purchased a partial back-up of DamageLab and reopened and rebranded the forum by leveraging the reputation they acquired during their time at Exploit.

Under the new name of XSS, the rebranded forum has flourished, despite users being acutely aware of the dangers of operating on a platform associated with an individual known to law enforcement agencies. Yarets, now released from prison, holds a legacy role on XSS and has recently even been appointed as a moderator of Exploit. The prestige and longevity of DamageLab outweighed the potential negative implications of restoring a defunct forum. At the same time, Ar3s’s experiences with the law are often called upon by other forum members, and his opinions are highly valued.

Operations and OSINT

The Wire also brings a dash of gritty realism to investigative operations. Rather than a Dr. House epiphany, catching criminals involves a lot of time, unglamorous and repetitive police work, and going down rabbit holes that often don’t pay off.

Much of this also applies to malicious cyber campaigns. When we think about the pantomime villains of infosec—advanced persistent threats—the industry tends to focus on how sophisticated these actors are, including the use of a flashy new zero-day exploit, or deployment of a rarely observed MITRE ATT&CK technique for example. However, the persistence of a threat actor is equally essential. Just like good police work, a stubborn and relentless threat actor is likely to find an opportunity eventually. Rather than just technical wizardry, cyber campaigns are often a game of unglamorous abrasion.

Investigations in The Wire also piece together various strings of often tenuous information. While none of these bits of information are a smoking gun on their own, it is their cumulation that eventually produces the satisfying “gotcha” moment that puts a criminal behind bars.

Just as Baltimore’s finest catch criminals through this process, criminals investigate us using the same methods online.

Many cyber campaigns begin with extensive reconnaissance operations. Threat actors will gather as much detail on a target individual or organisation as possible to conduct convincing social engineering campaigns through relatable phishing emails or to scope out the type of systems and devices that targets are using.

Again, much of this actionable information is pieced together from seemingly innocuous aspects of an individual’s online footprint. For example, a selfie taken by an employee and uploaded to their public social media page could have telling pieces of information to a trained eye. With a work badge, a laptop screen, and personal information like a mobile phone number and picture of a cycling hobby could provide all the information a threat actor needs to get initial access.

The Game is The Game

There are frequent references to “the game” within The Wire—i.e., the unwritten rules, codes, and processes of Baltimore’s institutions. The game is underpinned by a Darwinian logic—a kill or be killed mentality inherent to the drug trade.

The game is remorseless. Despite the toils, arrests, and deaths, the game continues. Drug dealers will be imprisoned, cops will continue to bust safe houses, and political scheming will launch new law and order policies. The game offers a pessimistic view of institutions and their ability to change the reality on the streets fundamentally. At the heart of the game is a story of regeneration and the enduring nature of the drug trade.

In many ways, the game mirrors the cybercriminal ecosystem. Police and security services have been highly active in targeting criminal messaging services, marketplaces, and automated vending carts (AVCs). For example, the prominent Dark0de forum was rendered offline by an FBI-led operation in 2015 while an international law-enforcement coalition took down Infraud in 2018, a half-billion-dollar operation selling hacking and fraud services.

Yet, the cybercriminal game plays on.

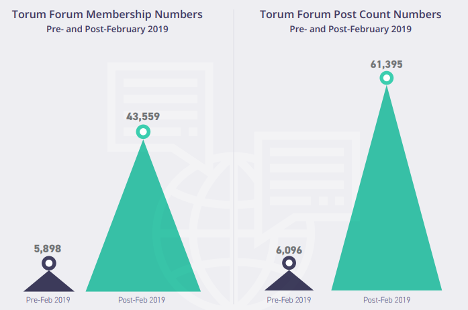

Despite both arrests and takedowns, criminals quickly migrate to new sites. For example, many threat actors would have hardly noticed when Torum entered the cybercriminal scene in 2017. It wasn’t until the disappearance of the popular KickAss forum two years later that threat actors started looking for an alternative, and the forum rose to prominence. By October 2019, Torum’s membership numbers had shot up to 43,559―a 639-percent gain in just eight months―and the number of posts on the forum had skyrocketed from 6,096 to 61,395

Death by Performance Metrics

An overarching theme of all five seasons of The Wire is the perils of performance metrics. Time and time again, public institutions are inhibited from doing good and important work due to a remorseless obsession with hitting absolute numbers.

For example, rather than doing in-depth investigations that would lead to arresting key drug kingpins, an obsession with boosting crime stats ahead of an election led to the police pursuing low-level (and mostly meaningless) arrests instead.

Much of this can also apply to cybersecurity and threat intelligence in particular.

There is no shortage of data in cybersecurity, and most organisations don’t need any more of it. There is ultimately little value in intelligence solutions that vomit data, publish irrelevant incidents, and regurgitate indicators of compromise without context.

Crucially, CTI must provide actionable insight that focuses on providing practical solutions and advice that can be readily consumed and integrated by intelligence consumers.

CTI can and should complement a variety of security and functions. For instance, tactical threat intelligence can complement an organisation’s vulnerability management approach; operational intelligence can feed into a security operations centre, while strategic intelligence can integrate into a company’s broader risk management processes.

With the parallels between The Wire and cybersecurity, practitioners should ensure that they devour all five seasons as soon as possible. More importantly, however, those that think Breaking Bad is the better series need to take a long hard look at themselves.

This blog originally appeared on Digital Shadows.